A 39-year-old woman presents to the ED with leg pain and fever. She initially noted redness and pain above her knee 2 weeks ago and was evaluated at an outside hospital. She completed a 10-day course of oral antibiotics for cellulitis. Over the last two days, she has had progressive leg swelling of her entire right thigh. The pain is now so severe that she is having difficulty walking. Her past medical history is negative for diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, or alcohol and IV drug use.

On exam, she is febrile to 102.7 F, heart rate is 96 bpm, and blood pressure is 112/65. She has a 12 cm area of faint erythema on her right thigh and tenderness to palpation of her entire right leg with diffuse edema. There is no ecchymosis or bullae formation.

She is admitted for IV antibiotics to treat cellulitis. Overnight, she complains of severe pain requiring multiple doses of narcotics. In the morning, a CT scan is obtained that demonstrates fluid and gas along the rectus femoris muscle. Surgery is consulted for debridement of necrotizing fasciitis.

She is admitted for IV antibiotics to treat cellulitis. Overnight, she complains of severe pain requiring multiple doses of narcotics. In the morning, a CT scan is obtained that demonstrates fluid and gas along the rectus femoris muscle. Surgery is consulted for debridement of necrotizing fasciitis.

Introduction

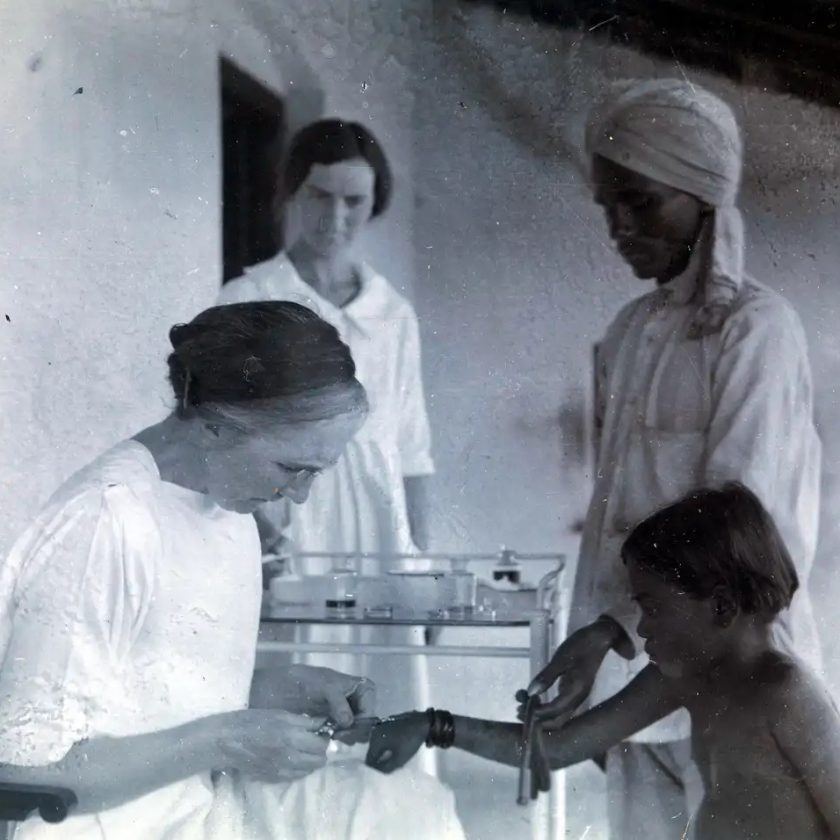

Necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTI) include necrotizing forms of cellulitis, fasciitis, and myositis. NSTI’s are rare but deadly deep soft tissue infections associated with tissue destruction, systemic toxicity, and high morbidity and mortality. The estimated mortality rate of necrotizing fasciitis is estimated to be between 25-35% [1, 2]. Necrotizing infections can occur anywhere on the body but most commonly affect the extremities, perineum, and genitalia, while rarely arising on the trunk [2, 3]. Infection requires inoculation with the bacteria, which typically occurs via a break in the epithelial or mucosal surface secondary to trauma, IV drug use, insect or animal bites, or surgery. However, it has also been reported without any known trauma in up to 17% of cases [4]. The rarity of the disease and lack of pathognomonic signs and symptoms early in its course make it challenging to diagnose. However, rapid diagnosis is essential because early surgical debridement reduces mortality and amputation rates [5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

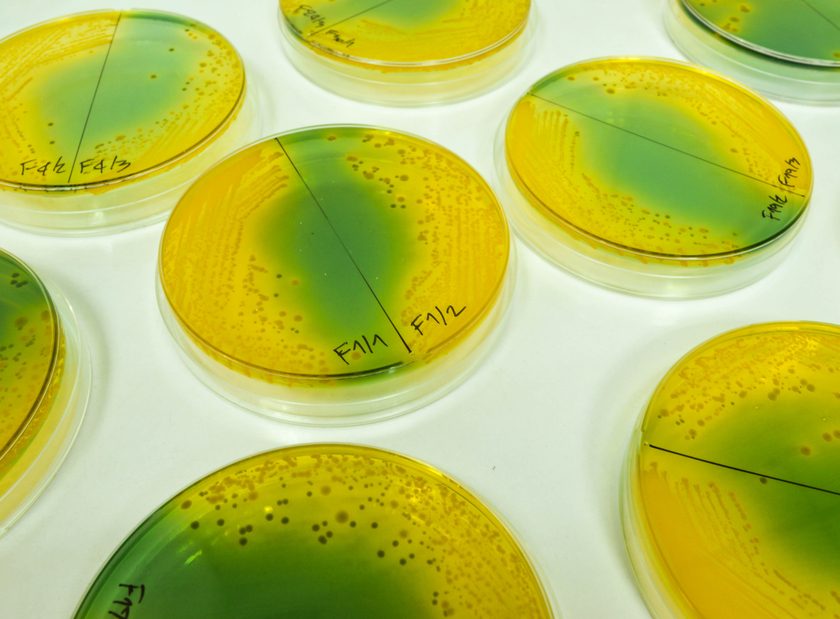

Necrotizing skin infections are classified into three groups based on the type of bacteria present. Giuliano and colleagues first described this classification system in 1977 [10]. It is important to note that each group has different risk factors and “classic” patient demographics, though these classifications are not exclusive.

- Type I infections are polymicrobial, which include gram-positive cocci, gram-negative rods, and at least one anaerobic species [2]. Common anaerobes include Bacteroides, Clostridia species, Prevotella, or Peptostreptococcus [11, 12]. Gram-negative organisms include Pseudomonas (particularly in immunosuppressed patients or those with malignancy) and Enterobacteriaceae [12]. Type I infections remain the most common. Patients with Type I infections tend to be older with multiple medical comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, obesity, immunosuppression, peripheral vascular disease, and recent surgery [4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12]. Fournier’s Gangrene is an example of a Type I infection of the perineum with bacterial sources from the skin, colon, anus, and rectum including coli, Klebsiella, Enterococci, and anaerobes. Diabetes is a major risk factor for Fournier’s Gangrene, but it can also occur after vasectomy in adults or in neonates with omphalitis or following circumcision [12, 13]. Clostridial infections (aka gas gangrene) are included in this category, but have decreased in incidence over time due to improved sanitation, although they continue to be reported among IV drug users injecting black tar heroin subcutaneously [14]. Infection with Clostridia species is characterized by rapid onset of symptoms after inoculation and is an independent predictor for limb loss and mortality [3].

- Type II infections are monomicrobial, most commonly caused by group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus alone or with aureus [2]. Patients tend to be younger and healthier and may have a history of trauma, laceration, burn, surgery, or IV drug use [8, 11, 12]. Necrotizing infections due to group A strep (GAS) can also be associated with toxic shock syndrome in about half of the cases [15, 16]. The virulence of GAS is determined by the M-protein, which has antiphagocytic properties [15, 16, 17]. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) can also cause monomicrobial infection in communities with a high prevalence [18]. Risk factors included current or past IV drug use (in 43% of patients), previous MRSA infection, diabetes, chronic hepatitis C and cancer and HIV [18].

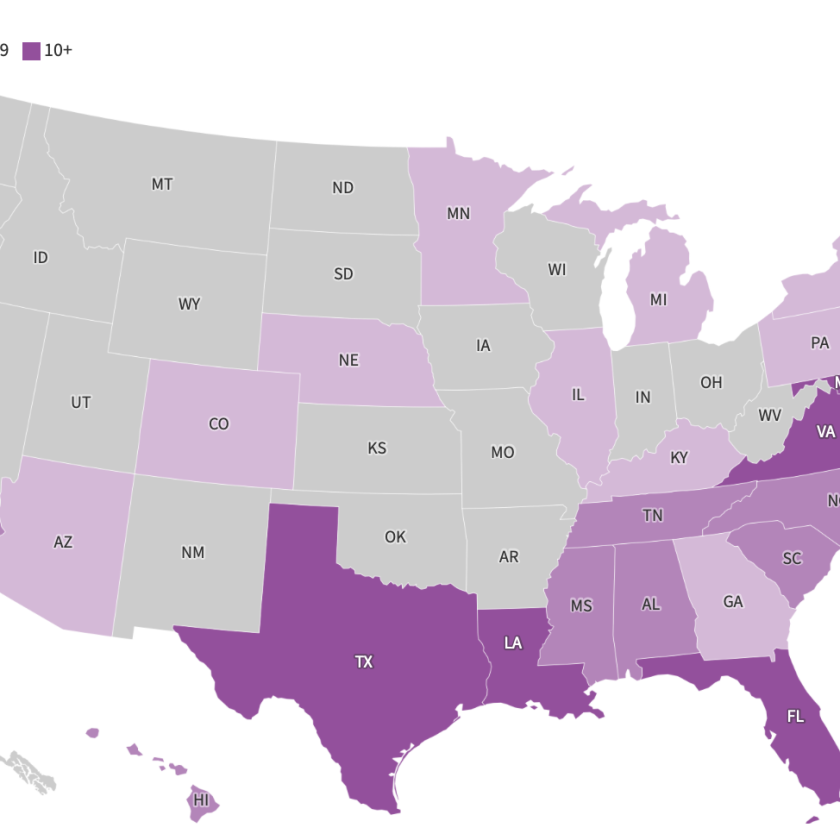

- Type III infections are caused by Gram-negative marine organisms. Infection generally occurs after an open wound or other break in skin is exposed to fresh or salt water. Aeromonas hydrophila is associated with wounds exposed to fresh water, whereas Vibrio vulnificuscan occur in seawater injuries or in a patient who ingests or handles raw oysters [2, 19, 20]. Risk factors include alcoholism and liver cirrhosis [20]. Type III infections have been reported along warm water coastal regions in the US, Central and South America, and Asia [2, 20].

read more emdocs.net